Why a National Trust dairy tenant moved to ‘holistic’ farming

Richard Park

Richard Park Farming to improve soil health, maximise production from grass and be self-sufficient is the aim of dairy farmer Richard Park of Low Sizergh Farm in Kendal, Cumbria.

His ambition is to manage the farm holistically, which incorporates financial planning, ecological monitoring and a regenerative grazing system into a decision-making framework.

Although he is only at the start of his journey, small changes to the farming system are already reaping some benefits.

See also: How mob grazing can be used to improve soil health

Farm facts

- 160 cross-bred cows plus followers (Holstein, Friesian, Scandinavian Red and Montbeliarde

- 150 sheep

- Second year of organic conversion

- Autumn block calving on a 12-week block

- National Trust tenant farmers

- 121ha split into one third cow grazing, one third silage ground and one third youngstock/sheep grazing

- Currently yielding 6,500-7,000 litres on 1.5t concentrates due to forage shortage over winter

- Slurry spread with trailing shoe

- Farm shop sells eggs from 600 free-range hens

What is holistic planned grazing?

Mr Park first heard about holistic management when he attended a course run by 3LM on the subject.

It is an idea that was developed by Zimbabwe environmentalist Allan Savory in the 1960s after studying the reasons for desertification in Africa.

He concluded if animals were managed in a way that simulated the natural behaviour of herds and wildlife, then habitats, water management and the condition of the land improved.

The concept is now practised globally. Holistic planned grazing considers the time that a plant is exposed to a grazing animal so that the recovery of the plant is planned.

The planned moves are usually shorter and faster during the fast plant growth period and slower during the slow growth and non-growing seasons. This is because the timing of the moves is driven by plant recovery.

It also ensures manure is spread more evenly and organic matter is incorporated into the soil by the trampling of longer grasses into the ground.

The longer grass also aids ground cover and, with it having an extensive root mat, the water infiltrates better, reduces flooding, doesn’t burn up as quick in drought conditions, and helps restore depleted aquifers.

It is different from mob and rotational grazing because it gives grass a longer recovery period. Mr Park says mob and rotation grazing systems don’t take into account the time needed for certain species of grass to fully regenerate, wildlife habitats and the water, mineral and energy cycles.

Why holistic planned grazing?

Mr Park felt holistic management suited his system as he has crossbred cows, is in organic conversion (converted by 2019) and has a limited land area as a National Trust tenant. He has also been rotational grazing for eight years, so a paddock system was already in place.

His ultimate aim is to position the farm in a place that is as removed from external influences as possible.

Mr Park says: “There’s a lot of change going on with Brexit and milk prices so I assessed the business and looked at our strengths. I decided to focus on producing as much as we can off the land we’ve got, but in a way that improved the health of the soils.

“One of the criticisms of organic farming is that it’s not productive enough, but my aim is to be as productive as a conventional system, if not better,” he says.

Putting a holistic plan together

After attending the course, the first thing Mr Park had to do was assess the land. During this he looked at ecosystem processes, such as the amount of decaying matter; percentage of bare soil; capping – whereby bare soil has been sealed by water; different species of grass; insect life; mineral flow and energy flow – for example, the amount of canopy/leaf area.

Although Mr Park felt he had a lot of technical experience, when he assessed the land he was surprised by some of the things he found.

“I was totally unaware of why ponding of water occurred in the middle of some established grassland, for example,” he says.“By assessing the land, I found out this was happening because of soil erosion. The fine soil was running down and sealing the soil surface, resulting in pools of water.”

Mr Park also discovered why docks were a problem in some areas.

“The thing with holistic management is that with every decision you make you always have to ask whether your decision is addressing the root cause of the problem.

Before organic conversion we would just spray the docks; however, this wasn’t addressing the root cause. When we assessed where the docks were we found evidence of compaction and also bare soil.

“Docks are nature’s way of trying to cover up bare soil. So, if we manage bare soils and compaction and increase the diversity of the plants we grow, then we are less likely to get domination by docks,” he explains.

Changes and benefits

Although much of what the Park family hope to do is based on theory, they are already seeing some benefits from the changes they’ve made on the farm.

Planned holistic management changes at Low Sizergh Farm |

||||

|

Aim |

Position before change |

What is the change? |

Reason for change |

Current position/benefit post-change |

|

Add more diversity to the silage and grazing ground |

Mostly monocultures of ryegrass with some clover |

Direct drill extra grass species such as Timothy and Fescues, more red and white clover, chicory and plantain as well as other herbs |

Nature needs diversity. Different species will offer better ground cover and aid community dynamics such as insect life. Different leaf surface areas will also help harvest energy from the sun. Plants with long tap roots will also help reduce compaction and survive better in dryer conditions. |

Due to the weather, they haven’t direct drilled yet. The hope is to complete it this year. |

|

Increase the grazing height at which stock enter |

Most land was grazed at heights of 2,800kg/dm/ha down to 1,800kg/dm/ha |

Cows entering grazing at 4,500-5,000kg/dm/ha and allowing roughly 30% of the grass to be trampled back into the ground (depending on individual paddock and the age of stock). Fence to be moved twice a day. |

Going in at higher grass lengths allows the different species of grass to fully recover. Trampled grass provides coverage and reduces bare soil. Also, the grass is broken down and provides nutrients for the soil. |

Have tried it this year with the youngstock grazing and found youngstock still achieving target growth rates of 0.8kg a day. In the hot summer, this land hasn’t burnt up to the extent other fields have. |

|

To produce rich fungal soils |

The ryegrass dominated swards are bacteria microbe dominant |

To support more diversity more fungi will be added to kickstart their growth. The fungi will be added through a sprayer. |

In order to increase diversity, you need a balance of bacteria and fungi microbes |

Not completed yet |

|

Introduce larger rotations |

Typically, a 21-day rotation – 39ha grazing platform with 160 cows |

Increase up to 60-day rotation in the growing season |

To allow grass to recover fully |

Have already introduced to youngstock grazing area |

|

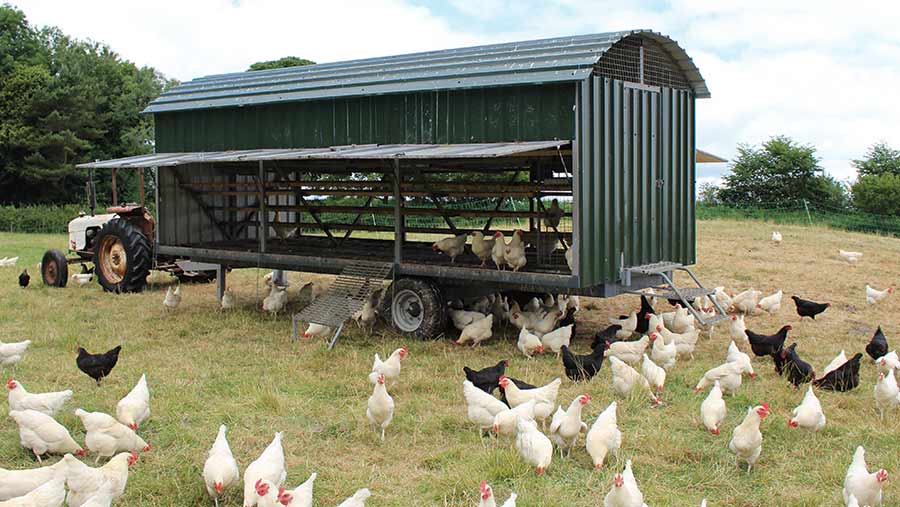

Introduced hens into the grazing rotation |

Their 600 free-range hens were housed on a dedicated range area |

Mr Park has constructed a mobile cabin, which allows the hens to follow the cows after grazing. Hens are shut into the cabin at night and then released the following day when they are moved into the next paddock. |

Hens are adding nutrients into the soil. They also scratch the ground and help break up the cowpats and spread them. Also adds variety into chicken diet as they pick larvae out from the cow dung, for example. |

Currently ongoing. Eggs appear to have a better taste as the hens’ diet is more varied. |

Mr Park says since entering organic conversion he has seen grass yields decrease as a result of not using bagged fertiliser. But he hopes this holistic approach to grazing will help combat this.

“We’d normally be averaging 10-11t/dm/ha, but last year this dropped to 8t/dm/ha/year,” he says.

“In four to five years’ time when we have implemented the holistic plan, we’d hope to be back up at 10-11t.

“Eventually, we would also like to be a 100% forage-fed herd.”

Key principles of holistic planned grazing

- Run as few herds as possible. One herd provides the best graze-to-plant recovery ratio (shorter grazing periods and longer recovery periods).

- Animals that remain bunched in a single herd are more effective at chipping the soil surface with their hooves and trampling down plant material to cover the soil so that air and water enter and new plants can grow.

- Scattered animals have less impact on the soil surface with their hooves and will create less litter to cover the soil surface. If animals – bunched or scattered – are left in any one place too long, or if returned to it too soon, they will overgraze plants and compact and pulverize soils.

- Plan plant recovery times before you plan grazing times

- Overgrazing is linked to the time animals are present, rather than how many animals there are

- Base stocking rates on the volume of forage available and how long it must last. Align it with carrying capacity – the number of animals the land can carry based on the forage available over the non-growing season plus a month or more of drought reserve.

- Plan on a grazing chart. This provides a clear picture of where livestock needs to be and when, and determines how managers plan their moves backwards or forwards.

- Create one plan for the growing season before main growth starts. The aim of this plan is to grow the maximum amount of forage possible during the growing season so that animals have enough to eat throughout the year and plants are not overgrazed.

- Create one plan for the non-growing season once grasses stop growing. The aim of this plan is to prepare the soil and plants for the coming growing season and to ration out the remaining forage over the months.

- Monitor the plan

Source: Savory